There is one detail about the exterior of Corpus Christi primary school in Limerick that you don’t notice until it’s pointed out to you. But once you do see it, it is striking.

This low one storey building, in the heart of Moyross, is completely exposed. Unlike the vast majority of schools across the country, there are no metal railings or brick walls and no gates for visitors – or vandals – to navigate.

But in all its almost 40 years in existence, the school has rarely suffered vandalism.

In fact, principal Tiernan O’Neill – 20 years working there – cannot remember the last time.

Nothing could bear greater testimony to the standing of Corpus Christi in its community than that.

Corpus Christi has three classes dedicated to children with significant additional needs; two for children with autism, and one for children with mild general learning disabilities.

But beyond that, in its general population of children spread across mainstream classes, it has an extremely high incidence of pupils with additional needs.

Moyross is ranked among the most disadvantaged communities in the country. The school reckons it has one of the highest allocations of special education teaching hours nationally.

As this week draws to a close, principal Tiernan O’Neill is furious at how, in his opinion, schools and their staff have been portrayed by ministers and others.

“Appalling” and “cynical” are the words he uses to describe what he views as an attempt this week by Minister Norma Foley to drive a wedge between school staff and parents.

“The support I have gotten from our community has been amazing. Where I lack support is from Government,” he told me yesterday morning by phone.

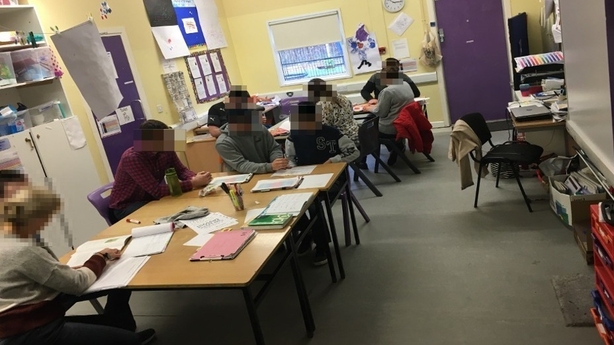

He said his school has been open since 4 January. Teachers have been in, preparing work sheets to deliver to children, holding classes on Google chat, and calling to the doors of families to check in with children and their parents.

Parents have been dropping by every day to collect work packs and consult with teachers.

Tiernan O’Neill, at the time we spoke yesterday, revealed that 10 teachers were currently in the school working. One was meeting a parent to discuss their child’s progress. Another four were out in the community calling to families.

In the past few weeks, Corpus Christi had purchased 50 laptops and tablets for pupils paid for by private donors. Additional state funding disbursed at the beginning of the pandemic last year covered the cost of just 25, he explained.

“Our home school liaison teacher called to the door of 120 children last week. By this afternoon he and other staff will have called to the homes of 200 children. They certainly do not want affirmation for this, it is what they do – but we do not want our vulnerable children to be used as a political football.”

Corpus Christi school was ready to open last Thursday and Tiernan O’Neill reckoned the school would have managed, but not without huge stress and anxiety on the part of staff.

He added: “Last April and May our calls for contingency planning fell on deaf ears and now we are left trying to cobble together a plan.”

Tiernan O’Neill’s anger is sustained throughout our conversation, and it is shared by other school principals. Other schools catering to disadvantaged children have been doing similar work.

“How passionate and focused they are suddenly on special needs, I really hope this passion and focus continues,” he said, referring to Government ministers.

The principal spoke of two-year delays for children at his school waiting for assessment and diagnosis of their conditions. He told of having to fundraise so children in need could access services privately.

Child mental health services in schools, he said, are “virtually non-existent”.

“When you look at the cuts in recent years to SNA provision, to special education provision. We have children in homeless accommodation, in direct provision.

“Now the gains that DEIS [Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools] schools have made are in serious jeopardy, and soundbites don’t cut it. We need clear decisive action.”

Corpus Christi school was ready to open last Thursday and Tiernan O’Neill reckoned the school would have managed, but not without huge stress and anxiety on the part of staff.

“Our children have to be back in school, parents want it, teachers want it, children want it, but we need a robust plan. Constantly repeating that schools are safe does not make schools safe.”

Tiernan O’Neill quotes Mike Ryan, Head of Emergencies at the World Health Organization – “the best and safest way to reopen schools is in the context of low community transmission”.

It’s a quote that many special needs assistants and teachers kept returning to last week.

A public health webinar was held on Monday with a view to reassuring school workers, but it failed abysmally.

Assurances in the form of factual information from public health officials – that infection rates in school age children are very substantially and significantly lower compared to the general population, that Covid levels being detected children in childcare facilities are also much lower – did not wash with those watching and listening, if the comments appearing on screen during the webinar were anything to go by.

Those comments came so thick and fast it was not always possible to read them, but they seemed entirely negative.

“Propaganda, rubbish, lies” read one message that was representative of the overall tone.

The message that did seem to be absorbed was one that many SNAs and teachers were already highly conscious of and that was the very real connection between schools and their communities, and the threat that high levels of infection in the community poses to schools.

Notwithstanding this, Tiernan O’Neill still wants his school to open, and he is worried.

“We are five school days away from 1 February, when schools were supposed to reopen, and there has been not a smidgen of information. There is no plan.”

He wants schools to be allowed to make their own decisions locally.

Limerick’s 12 or so DEIS schools have banded together, in a forum somewhat ironically called “Oscailt” (the Irish for ‘open’).

“There are networks like ours all over the country,” he said. “The needs of a large urban Band 1 DEIS school are different to a two-teacher school in the country.

“If the DEIS schools in Limerick were given the autonomy to sit down locally with public health here and work it out we would find a solution that actually works for us in our school.

“Schools have to reopen. It can be done, but we have to balance the health and safety of the school community with the learning needs of the children in our care.”

‘I would call our school prefab a kip’

There are 133 special schools listed on the Department of Education website. These generally small schools cater exclusively for children and young people with profound or significant additional needs.

These needs can be intellectual and physical. There are 39 of these schools – that’s 30% – listed on department building lists with 27 waiting for a full new school building and 14 for large extensions.

To get on to a Department of Education building list in the first place, a school’s need has to be great, yet almost one third of our special schools are in this category. This is a disproportionate number compared to mainstream schools, but even this is not the full story.

Stepping Stones Special School in Co Meath would seem in dire need of a new school building but it has not yet even made it on to any departmental list.

The school was established by parents around 20 years ago. It began life in a classroom borrowed from another school, then it moved to a temporary home in a bungalow. In 2004, parents took out a loan to buy a prefab, and 16 years later that prefab is still its home. The school has 30 pupils.

Olive McClean answered the phone when I called the school yesterday. She is the school’s administrator.

“I would call it a kip,” she told me. “We had issues where there was water coming in from the roof. There are stains on the ceiling tiles. The floors in some of the classrooms are sinking in. They are rotten. There are holes in the walls.”

Stepping Stones caters for children with autism and complex needs aged between four and 18 years of age.

A technical report was carried out on behalf of the Department recently and the school is now waiting to get onto the waiting list for a school building.

Olive McClean, too, is livid, and she is only too happy to give her view to RTÉ.

Referring to some of the discourse of the past week she said: “The backlash has been absolutely disgusting. Everybody here is devastated by the situation yet they are making out that the staff don’t care. Everybody seems to have forgotten that this is a killer virus.”

Olive McClean does not, herself, work in the classroom but she speaks to me about what she sees. She speaks of the struggle to access “very limited” services such as occupational and speech and language therapies and the fact that families often have to pay to go private.

Some of the pupils at the school are prone to aggressive behaviour. “Staff get injured here but they carry on because they care about the children.”

Of the Government she asks: “If they care that much why don’t they do something about our school?”

‘The teachers are very good, they are ringing every day’

A mother at Corpus Christi spoke to me on condition of anonymity. She has three children, two of whom have autism.

Of her eldest child, who has autism, she said: “He’s gone back into himself. He has stopped socialising. He has stopped getting dressed. He is in his pyjamas.

“He loves school, he loves his academics, but at home I can’t help him, and I have the others to mind too.

“I am educated, but maths is not my strong point. He is doing long division and decimals and I can’t understand them.”

This mother received a tablet from the school but she prefers her son to use work sheets “because when he is online he goes on to YouTube.

“The teachers are on call. They are very, very good. They are ringing every day.

“If the teachers of Corpus Christi want to get back, why can’t we open our school and leave the kids back?” she asked.

Chatting on the phone, this mother – let’s call her Anne – described the school. She has only high praise for it.

“The kids call by and say ‘excuse me sir can we have a ball’ and Tiernan will give them a football, and it will be clean (sanitised) and everything.”

She talked about how the school is so much more than just a school. Corpus Christi hosts adult education classes, line dancing for the elderly and cookery classes.

It is a lifeline for the community and has been a lifeline for Anne.

“I started out in the adult education. I did mindfulness, DIY, beauty, woodwork.” Then the school suggested she go further. Now Anne is in her second year of a degree course in Social Care at the local institute of technology.

“I know it’s a struggle with everything, but I have to keep studying!” she said. “I will have a placement this year and there is no leeway!”

Anne is driven. But she said other parents in the community who are coming up behind her on the same pathway are suffering because they have lost their adult education.

She is worried about the impact this is having on their mental health.

“They are saying ‘that’s my time away from the kids’. Just to get your brain away from your kids and your household and everything. That’s your own mental health.”

Long-term concerns about the system

Tiernan O’Neill, Olive McClean and Anne all want the same thing – and it is what Government and the Department of Education want too.

They want schools back up and running as soon as possible, most especially for those vulnerable children with additional needs.

But for them the past week has highlighted and even heightened more long-term and wider concerns.

Concern about divisions in schooling here, concern about the fact that, as they see it, their children and their families have always been the poor relation.

They are used to it. For them, this week was not the first time that the system failed them.