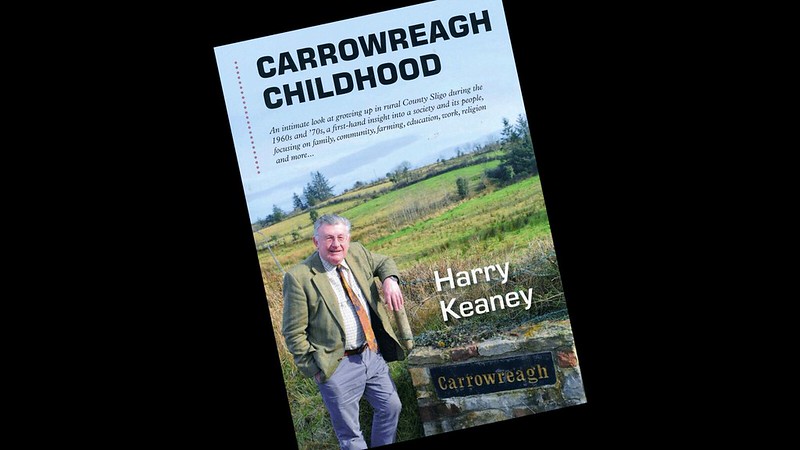

CARROWREAGH CHILDHOOD

A new book by HARRY KEANEY

For further information, images or to arrange author interview, contact 087 956 5613 or email carrowreagh123@gmail.com

On the 29th of June this year, Sligo native Harry Keaney completed four decades working as a journalist. To mark the occasion, he has just finished writing a new book, entitled Carrowreagh Childhood.

Of course, it’s not uncommon for journalists to write books to mark major events, milestones, anniversaries and so forth. When it comes to the highlights of journalistic careers, the books usually focus on the big stories covered, places visited, events witnessed, people met and interviewed, as well as what lessons might be learned, if any, from looking back with the benefit of hindsight.

Two years after Harry Keaney began training as a reporter in 1981 with the Roscommon Herald newspaper, he was at Derrada Wood, near Ballinamore in Co. Leitrim, where the IRA had held the kidnapped supermarket executive Don Tidey.

In Roscommon at the time, there was the colourful and controversial Roscommon TD and later Justice minister Sean Doherty, with Harry remembering the competition between he and party colleague Terry Leyden having been as intense, if not more so, than if they were opposition party politicians.

In the U.S., while he was working for the Irish Echo newspaper in New York, Harry saw the hugely influential groundwork being laid for the eventual signing of the Good Friday Agreement. Among his assignments was to be in the arrivals hall of John F Kennedy Airport in New York on the afternoon of Monday, January 31st 1994 to report on the historic arrival of Sinn Fein Leader Gerry Adams after President Bill Clinton had approved a temporary visa to enable him visit the U.S.

Back in his home county newspaper The Sligo Champion ten years later, Harry saw firsthand a generations-old system of newspaper publishing swept aside by the modern as media corporations went on a spending spree acquiring locally-owned publications.

But the big stories from Harry’s four-decade career in journalism are not what he has focused on in his new book.

Instead, he returns to his roots in south east rural County Sligo, to his native townland of Carrowreagh (An Cheathru Riabach, the grey quarter), the nearby village of Riverstown, his attendance at secondary school in Boyle on the far side of the Curlieu Mountains in County Roscommon and, finally, getting a job with the Roscommon Herald newspaper in 1981.

Carrowreagh Childhood covers a period of just 18 years and is part family record, social history, occasional commentary and more. The book was printed on the 29th June this year, exactly 40-years to the day since Harry walked into the imposing offices of the Roscommon Herald, then on St Patrick Street in Boyle, where Mrs Lily Nerney was the owner and Micheál O Callaghan was the editor.

Harry agrees Carrowreagh Childhood is very local and very personal. Castlebar-based award-winning designer, creative consultant and marketing expert Siobhan Foody has even incorporated personally-connected detail into the production of the book. For example, it is typeset in Plantin and Eurostile, which was created in 1962, the same year as Harry was born.

It is this appreciation of the past that sets Carrowreagh Childhood apart, a book described as not only about rural life in Sligo in the Sixties and Seventies but also about the everyday practicalities of actual living.

Harry says: “Sometimes, people are reluctant to talk about the past for a variety of reasons but I believe it’s important they do, and that people and their past become part of the greater record.

“As I wrote in the introduction to Carrowreagh Childhood, I am an only child, a link between generations. Therefore, I have felt an urge, an obligation almost, to write this record.

“And yes, it is very local, personal and detailed in parts, even down to field names. But I think this detail should not be lost, even if some people think it’s not important just now. In 50, 100 or 200 years hence, this very-focused account will give an insight into not only rural life but also into everyday living in south east county Sligo in the 1960s and 1970s by one who was part of it.”

The book covers what were the main activities in the area in which Harry grew up, the main one having been farming. It also focuses on family, community, school, religion, work and more, all creating an endearing account that will evoke heartfelt memories of a bygone time.

Harry also sees Carrowreagh Childhood as a way of honouring, paying tribute, giving a ‘proud salute’ to what could be called the ordinary people who were around when he was a child.

However, ‘ordinary’ is not a word Harry is enamoured with, particularly when applied to people and their lives.

He says: “No person is ‘ordinary.’ Everyone is unique and special. I always smile to myself when I hear someone described as ‘extraordinary.’ Imagine, extra ordinary, and most people regard this as a compliment.

“No, I think the so-called ‘ordinary’ people, the people around me when I was a child, deserve to be remembered as the VIPs. I see the book as a tribute to those people, some now dead, many still alive. People who, normally, would never feature in a book.

“Out in rural Sligo, the man who cut the meadow and helped you save the hay was a VIP. So too was the man who brought home your turf with his tractor and trailer, the man who bought the milk to the creamery, the hackney driver who brought people to Mass on Sundays or to Knock Shrine between August 15th and September 8th, the postman, the shop-keeper, butcher, undertaker, teacher, local doctor, the handyman who helped with a sick farm animal when you didn’t call the vet, the women and men who helped in times of need or gave encouragement . . . these people were not ‘ordinary.’ They were the people who kept the cogs of society moving, often in difficult circumstances. They were integral parts of a rich community, all interlinked to create the environment – with its good and bad times — in which people like I grew up, and from which we got our values.”

Carrowreagh Childhood also looks back on the secondary school education system in Boyle that Harry became part of in September 1975. Again, he believes it’s something that should not be forgotten.

He explains: “It was an innovative system at the time involving cooperation between the secondary and vocational sectors, resulting in students getting the benefit of both. It was really an experiment in education that eventually became departmental policy. There was something very special about education in Boyle at that time, not only in the model adopted but also in the ethos imparted.

“There were all those people who mould you along the way. Parents, of course. Neighbours. Local people you meet. And teachers, one of whom was very influential in my case, leading me, eventually to a career in journalism, something that was a bit bewildering at the time to my parents who a few times asked, ‘Can you not get a right job like everyone else?’ I can tell you, during 40 years since, it’s a question I have often thought about.”

Harry admits that thoughts of writing a book like Carrowreagh Childhood had been gnawing at him for years.

“I had the urge for a long time to write a book like this and then get onto writing other things. I recall many years ago while attending a funeral – I think it was in Highwood – a man made a remark to me that really stuck. We were all standing around outside talking quietly about the life of the person who had died. As the crowd silently followed the coffin in the doorway to the church, the man I had been talking to prodded me in the back with his finger and whispered, ‘And did yerself ever think of writin’ an auld book about yer own people?’ I laughed and dismissed the idea, to which he curtly responded, ‘Ya should be shamed of yerself.’

“As I said, the remark stuck. What’s more, it was the family history I wrote first but when it came to laying out and designing Carrowreagh Childhood, those chapters ended up in the latter part of the book.”

Harry started working on Carrowreagh Childhood in September 2017 but it wasn’t until he was off work at the start of the Covid pandemic that he made real progress on it.

“I copied the discipline of other writers I’d read about, putting in almost the same hours every day as if I were working fulltime at my job with Ocean FM Radio.

“I think there was also something special about writing much of the book in the house, in the townland, where I grew up. Small, rural townlands like Carrowreagh, where fewer than 15 or so people are now living, are rarely written about, unless it’s for something such as a death notice, a planning application, ESB outage, maybe an auction or land sale.

“Now I have ‘Carrowreagh’ emblazoned in the title of a book, with the place, its time and people immortalised between its covers.”